Roadtrip 2017 – Exploring The West – Day 10 – July 19th – Part 1:

After spending the night in the truck, Marley and I were on our way to Mount Saint Helens. I remember when it erupted in 1980, and the destruction it left behind.

We headed south on IS-5 roughly 20 miles to SR 504, and then followed that east to Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument.

This is a beautiful area, but the landscape is different now than it was prior to the 1980 eruption. I believe that you can’t really appreciate something if you don’t know what you’re looking at, and things can take on a whole new meaning when you understand the story behind them.

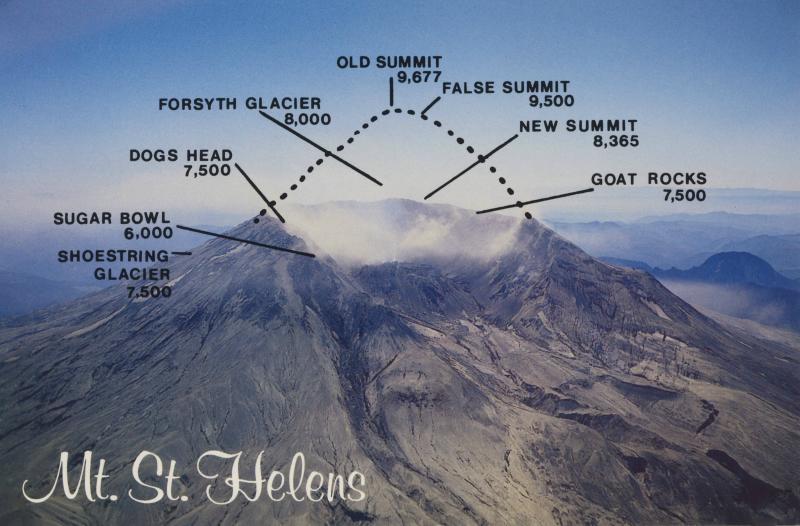

Above you can see the crater left by the eruption.

Below is a photo of it prior to its eruption. It’s hard to believe it’s the same mountain

(Mount Saint Helens before the 1980 eruption)

Mount Saint Helens erupted at 8:32 am on May 18, 1980. Instead of erupting straight up from the top, the volcano experienced a lateral blast from the north face of the mountain. Hot ash and rock shot out at speeds upwards of 300 mph, some 12-15 miles into the sky, creating a mushroom-shaped plume of 540 million tons of ash. Cities and towns across Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana and beyond were blanketed by 3-5 inches of ash. Spokane, Washington, about 250 miles northeast of the volcano, experienced complete darkness.

57 people lost their lives. Approximately 250 homes, 47 bridges, 15 miles of railways, and 185 miles of highway were destroyed. Heavy logging trucks and machinery were catapulted and displaced as if feathers in the wind. Over 200 square miles of forest was either liquidated or knocked over leaving a barren and scorched earth.

(Photo of trees blown down after the 1980 blast)

Thousands of animals were killed instantly, and an ecosystem was forever altered. The beautiful Mt. St. Helens summit was replaced with a one mile wide and 2,084 foot deep horseshoe-shaped crater, shaving the elevation of the summit from 9,677 to 8,366 feet.

Snow and ice on the top of the mountain melted instantly, creating a raging debris avalanche of water, mud, and rocks barreling at speeds over 155 mph. It swallowed everything in its path including the entire surrounding forest. Covering an area of about 24 square miles, the avalanche advanced more than 13 miles, filling the valley to an average depth of about 150 feet.

In the photo above, you can see where this area was filled in with 150 feet of mud and ash. The Toutle River flows here, but was filled in during the eruption. Rain, snowmelt, and a mudflow from a 1982 eruption carved new channels in the valley.

When you visit here, you can still see evidence of the 1980 blast. Although the area has been repopulated with trees, there are still areas where you can see evidence of them being blown over, as well as the results of the ash and mudflow as seen above.

Remembering Those Who Perished:

There were 57 people that perished from the eruption. Some as far as 11 miles away. Some died in their vehicles. Some were never found, and some of their vehicles were never found either. Here are the 3 most notable ones you’ll hear about.

David A Johnston, 30: When you get to the end of SR 504 you’ll come to the Johnston Ridge Observatory. The observatory (and the ridge it sits on) is named after USGS Volcanologist David A Johnston. Johnston was killed in the eruption while manning an observation post at this location on the morning of May 18, 1980. He was the one who feared St. Helens the most, and repeatedly warned people; referring to it as a “dynamite keg with the fuse lit”. His warnings may very well have saved thousands of lives. David was the first to report the eruption, transmitting “Vancouver! Vancouver! This is it!” before he was swept away by a lateral blast. Despite a thorough search, Johnston’s body and vehicle were never found, but state highway workers discovered remnants of his USGS trailer in 1993.

The observatory hosts interpretive displays that tell the biological, geological, and human story of Mount St. Helens. Visitors to Johnston Ridge Observatory can enjoy multiple award-winning films, listen to ranger talks, observe the landscape, purchase souvenirs, set off on a hike, or get a light lunch from the food cart.

What’s truly mind blowing is to stare at the crater of the volcano, realize how close it is, and imagine that this is where David Johnston was observing it when it erupted and swept him (and the trees) away.

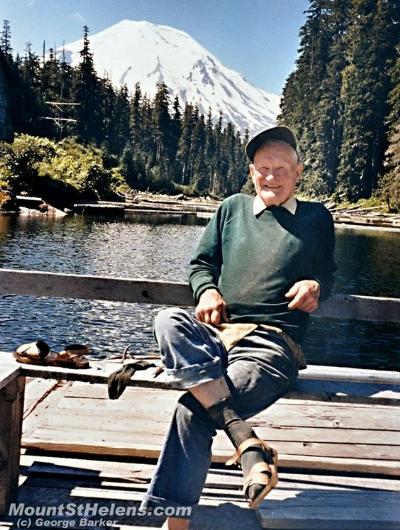

Harry R. Truman, 83: Harry R. Truman was the long-time owner and operator of the Mount St. Helens Lodge, which was on the southern shore of Spirit Lake beneath the northern flank of the volcano. When the first earthquakes occurred under the mountain in March 1980, he became a national celebrity for refusing to leave his property. When asked what he would do if Mount Saint Helens erupted, he stated “I’d stay right here and watch it. It’s too far away from me. Couldn’t hurt me. Hell, it’s a mile to here and it’s all heavily timbered in here….it couldn’t get to me”. When Mount Saint Helens erupted, Harry and his lodge were buried under several hundred feet of avalanche debris, and were never seen again.

‘Harry’s Ridge’ is named after Harry R. Truman, and can be accessed by a hiking trail from Johnston Ridge Observatory

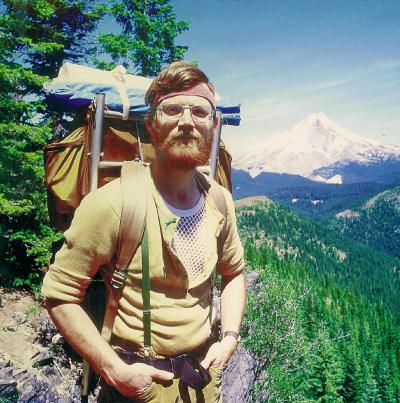

Reid Blackburn, 27: Reid Blackburn was a photographer for the Columbian newspaper in Vancouver, Washington, who was participating in a project arranged by a freelance photographer for National Geographic. When the volcano erupted, he was able to take a few photographs before jumping in his car. But before he could drive away, the car filled with ash and he died of suffocation. All of his photographs were destroyed by the heat of the blast cloud.

In December 2013, a roll of undeveloped film containing pre-eruption shots of Mount St. Helens was discovered in Blackburn’s archives at The Columbian. The photos, taken by Blackburn during a helicopter photo shoot of the mountain the month before the eruption, were successfully developed over 30 years after Blackburn’s death, and remain journalistically important as a record of the pre-eruption landscape.

Still Active – Never Forget:

While the volcano is mostly known for its 1980 eruption, it’s last activity was in 2008. Mount Saint Helens experienced a continuous eruption from 2004-2008. On January 16, 2008, USGS geologist John S. Pallister spotted steam seeping from the lava dome in Mount St. Helens’ crater. At approximately the same time, the Pacific Northwest Seismograph Network recorded a magnitude 2.9 earthquake, followed by a small tremor that lasted nearly ninety minutes, and a magnitude 2.7 earthquake. On July 10, 2008, it was determined that the eruption that began in 2004 had ended.

If you get a chance to go to Mount Saint Helens, remember that this is still considered an active volcano.

Remember David Johnston as you look at the volcano from the Johnston Ridge Observatory. Remember that him, his vehicle, and his trailer were swept away, but only remnants of his USGS trailer were found 13 years later.

Remember that Harry Truman and his lodge are buried under hundreds of feet of mud and rock.

Remember that there are still people and vehicles missing.

Remember everything that was lost, to truly appreciate what you’re looking at.

After spending some time admiring Mount Saint Helens, it was time to head north. We weren’t that far from Mount Ranier, and I wanted to visit the area before it got dark.

Links:

Roadtrip 2017 – Exploring The West – Day 10 – Part 2

Roadtrip 2017 – Exploring The West – Main Page